Investment Scams & why we continue to fall victim

What are investment scams?

BLQ Football (2019 – 2022) - On the surface, BLQ Football operated as an elite betting platform that allowed its members to make money through their ‘secret formula’ that ensured profitable bets as high as 4% compounding interest daily. For a while, money was flowing and even when members lost a bet, the platform compensated them; further attracting new recruits. Entrance into high-interest and privileged tiers became sought after (starting at UGX 1 million).

By the time of its collapse, an estimated UGX60 billion ($16 million) that had been collected in the Ponzi scheme, was gone in the wind and thousands of Ugandans were embroiled in one of the biggest scams the country had seen. This was only the latest in a string of scams that continue to wreak havoc in communities and damage the possibilities for an environment where legitimate investment can thrive.

Two peas in a pod:

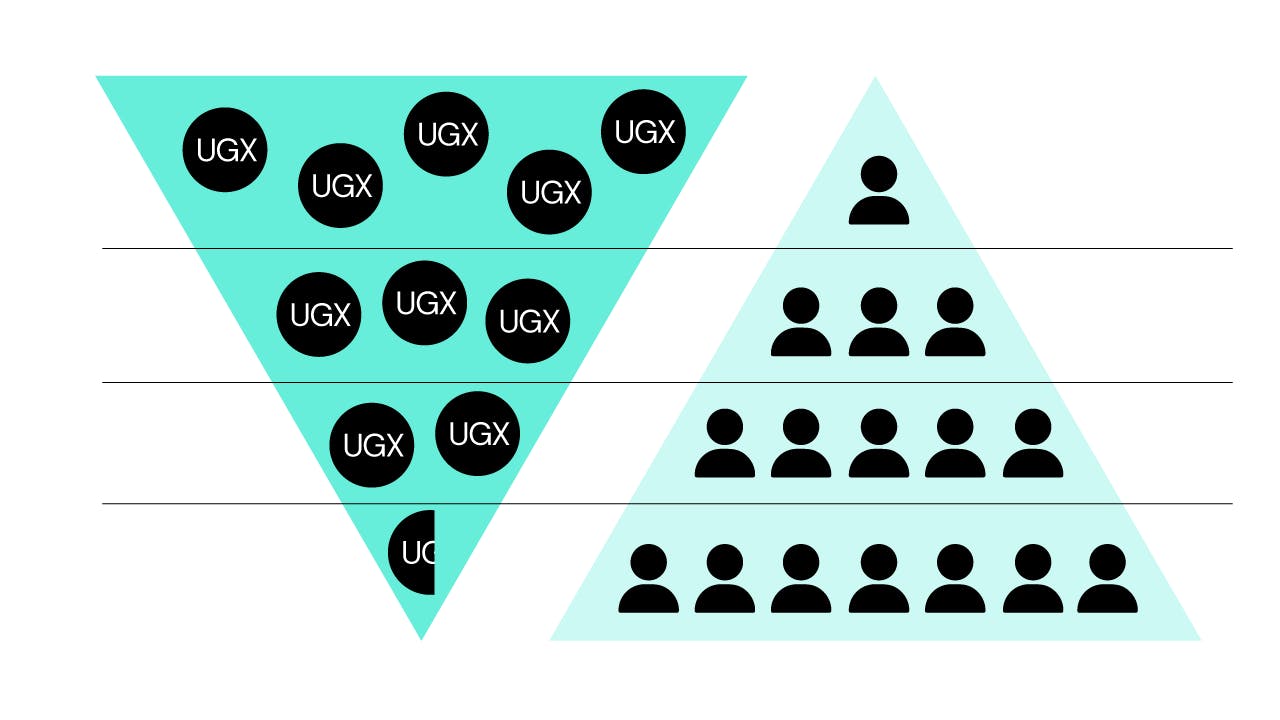

Ponzi Schemes are named after Charles Ponzi. In the early 20th century, Mr. Ponzi convinced investors that they would get a 40 to 50% profit on their investment. Early investors received payouts as promised using funds from later investors.

The scam can grow for months or even years, as more investors, are lured in by stories of huge payouts until the truth gets out and ‘investment’ stops. Pyramid schemes operate in a similar manner with the unique component of ‘making money’ by recruiting more people into the scam.

Investment scams exploit the innate greed that runs deep in human beings. The schemes themselves take many shapes and forms as scammers whip up new ways to dupe the public. But care to dig a little deeper and you’ll be met with ambiguities at how the ‘investment’ makes money. Their unconditional trait is their bait: return on investment. This is also where you can notice the red flags.

TelexFree (2013 – 2014) - TelexFree set up shop in Kampala in 2013 as an online marketing firm headquartered in Brazil, the only detail its newly forming membership paid attention to was its 30% monthly return on investment. The model was you invest money and get up to 30% per month return provided you can recruit additional participants and earn commissions for each recruit. A typical pyramid scheme. Nonetheless, it attracted hundreds of people who invested millions of shillings.

In both examples very little or no explanation was given on how returns were made; the emphasis always on the ‘how to join’ and how much you will get paid. This is a major warning signal because the underlying profit-generation activity should be clearly laid out.

Why do we keep falling for them?

According to studies done in psychology, there are key factors that contribute to us falling for scams.

- Individual Behavior: Case studies show that individuals with a lower ability to regulate their emotions and a higher degree of impulsiveness are more likely to fall for scams. This is highly exploited by scammers who use emotional appeals to attract and dupe victims. However, there are other characteristics that leave people susceptible to scams, including lack of skepticism and overconfidence in their ability to detect scams.

- Social Influence: People are more likely to fall for scams when they are presented with a level of social influence. This is due to the underlying use of social proof. Most people will act if they have seen the scheme work for others, especially people they like or admire.

- Perceived legitimacy: Scammers ride on the power of authority to control and influence compliance.

- Scarcity: Studies show that people are more likely to find something appealing when they have it in short supply. Scammers can take advantage of the economy or even engineer their sense of lack, for example, branding it as a limited offer to influence the public.

- Reciprocity: Studies show that when someone receives something, they feel obliged to reciprocate. For example, social psychologists have found that giving a mint at the end of a meal can increase tipping by 20%.

Beyond the blow of losing their hard-earned savings, victims of investment scams are often isolated in the complex task of unraveling the schemes that targeted them; most choosing to cut their losses quietly and move on. It is no surprise therefore that ‘monies obtained under false pretense’ as it is termed by the Uganda Police Force continues to rank first among economic crimes, rising by 6.6% between 2020 and 2021, with little hope of recompense for its victims.

As the nature of investment scams advances with available technology and reaches larger parts of the public, the ability to identify warning signs must keep up the pace. Responsibility to carry out thorough due diligence before one acts, needs to take place at an individual and societal level. So, the next time you are presented with an ‘opportunity’, remember to check the underlying profit methods before you buy into the returns and become yet another investment scam statistic.